Muslim Valencia fell to the Christian forces of James I of Aragon in September 1238, marking the end of +500 years of Muslim rule since the first forays from North Africa in the early 700s AD. It would take another 250 years of Taifa spats, back-stabbings, briberies, and battles between the regional fiefdoms and kingdoms of Andalucia until the Nasrid Dynasty was ousted from the mighty Alhambra in 1492 by the Catholic Kings. 750 years of Arab-Muslim rule of different parts of the Iberian Peninsula that culminated in an abundant legacy of hybrid languages, infused architecture, and shared histories surrounding the control of the same territory. The Jews were also present, but always as a minority. The ivy emblem is supposedly a Hebrew design element that is on a Muslim column in the Iglesia San Juan del Hospital that attests to the Jewish presence co-existing amongst Muslims and Christians alike in the 10th century: a Hebrew design on a Muslim column in a Christian church. Within this fabric of time and palimpsest of religions, the Knights Hospitallers and the Templars played a “relevant” role in the 12th and 13th century conquest of Sharq (eastern) Al-Andalus from the Moors. (Enric Guinot, “El Orden de San Juan del Hospital en la Valencia medieval”, p.722)

The Biblioteca Historica is located in the +500-year-old University of Valencia (UV) main building for the arts and culture. You explain the ongoing search for sources on medieval hospitals to another receptionist who is kind enough to walk you through the courtyard that is baking in the sun where hordes of students and teachers are conversing so loudly that their voices form a uniform sea of sound, the sound of static energy or birds chirping in an aviary, of people chattering all together simultaneously, like the water rushing in pipes. There is a strange feeling to walk on the almost slippery stones of the sun-drenched courtyard while waves of sound are showering down cheering all around you and the little receptionist who says “right over here past these doors” as she pushes past people talking loudly in the shade of the arcade before a great black door she knocks on and enters, leaving you now, inside what could be a library entrance but could also be a stale doctor’s cabinet.

Two pale-faced librarians emerge from behind a partition and provide the support they can for your inquiries into medieval hospitals. They simply do not know what you are talking about, nor whom you should talk with, so they refer to the digital library resources where you can find all resources and make bookings for visits ahead of time. “Yes, but I am here now, so if we could go into the library and do a search together…” We cannot do that, they say in unison, agreeing with each other, that this would be most unorthodox to allow a stranger inclined to such random improvisations to disturb the order of bureaucratic processes. You recognize the absurdity of being there in person and not being able to enter without a digital approval form, and you realize that things are changing and that if everything is becoming digital and virtual then what is the point of doing the real thing? On a positive side, you can receive all the resources you need via their portal, but on the negative side, if you had not come in person, then you would not have seen the splendor of this university.

And you would not have seen La nave de los locos. Una odisea de la sinrazón (2022) on display in the glass window of the university shop that was closed as you strolled around looking for the Library. “Well,” you venture with the two librarians, “when will the shop be open?” They don’t know that either but one of them seems to take pity on you and gives you the address and phone number of the University Bookshop that is near the Clinic Hospital where you were yesterday. You smile at the thought of walking back across the gardens of the dead river at this time of day when the sun is hottest and some people are sunbathing on towels, others are taking a siesta in the shade, others are doing exercises, and you think of the Knights Hospitaller and how they went in the silver armor from Jerusalem to Rhodes in 1309 where they were ousted by the Ottomans in 1522 and then found refuge in Malta until Napoleon routed them on his way to Egypt in 1798, but that was 500 years later, so what were the Knights Hospitallers doing in the Iberian Peninsula?

The Knights were certainly supporting the Christian forces as part of the endeavor to conquer more territory from the Muslims, and to consolidate their gains by repopulating with Christians, and via the institutionalization of care centers that were the early forms of hospitals. In each place, the Knights would build hospitals to care for the sick as part of the Christian ideal, consolidate the conquest with providing care and security for society: they were holy warrior-monks. In Jerusalem, Christian monks settling with the First Crusaders built a hospital in 1080 to care for the many pilgrims falling ill during their travels to the Holy Land; then the Order of St John of Jerusalem emerged to provide medical care and a form of military protection. The St John of Jerusalem Hospital became known as the Muristan area in the Old City of Jerusalem. There must have been different branches of the Knights Hospitallers: if they started in Jerusalem, then they must have crossed the sea rather quickly to settle and build a church-hospital, or they came around by land… You must find out more. These Christian hospitals were certainly not maristans (there is a confusion of nomenclature in Old Jerusalem) but they share the goal of caring for the poor and sick, and they share a timeline, competing for dominance and relevance in that space of history.

You thank the two librarians and head out towards the shade of the gardens. By the time you make it to the Bookshop your brow and back are sweaty. La nave de los locos is waiting for you on the counter but you prefer to cool off and walk around the medieval section of the bookshop where you discover a bunch of books on hospitals and health that are all in valenciano. You pick up a book about the Order of St John of Jerusalem and their time in Malta. You need to go back there and find the hospitals. If these warrior-monks were truly good, then certainly they must have cared for the mentally unstable as well or was it that mental illness was more meshed into society in medieval times? You leave the history book for another time and pay for La nave de los locos (The Ship of Fools) and head out to find a café in the shade somewhere of a great ficus or plane or jacaranda tree.

You flip open La nave de los locos and read through some of the passages describing how madness was treated in Valencia through the ages, acting as a microcosm of larger trends occurring throughout Europe and beyond: the advent of the first hospitals for the mentally disturbed, the institutionalization of insane asylums slowly but surely categorizing and ostracizing those affected by fleeting mental fires to wards and locations outside the view of society, then the modern advent of psychiatry and the study of psychology and the further categorization and drugification that these categories implied: medication, pills and other chemical potions, would help solve the mysteries of the mind, but the more medicine tried to help, the more the mind rebelled: you can’t treat an illness that is a natural condition for some by shackling and zapping the traits; you have to allow for the freedom of expression and provide the empathy of care.

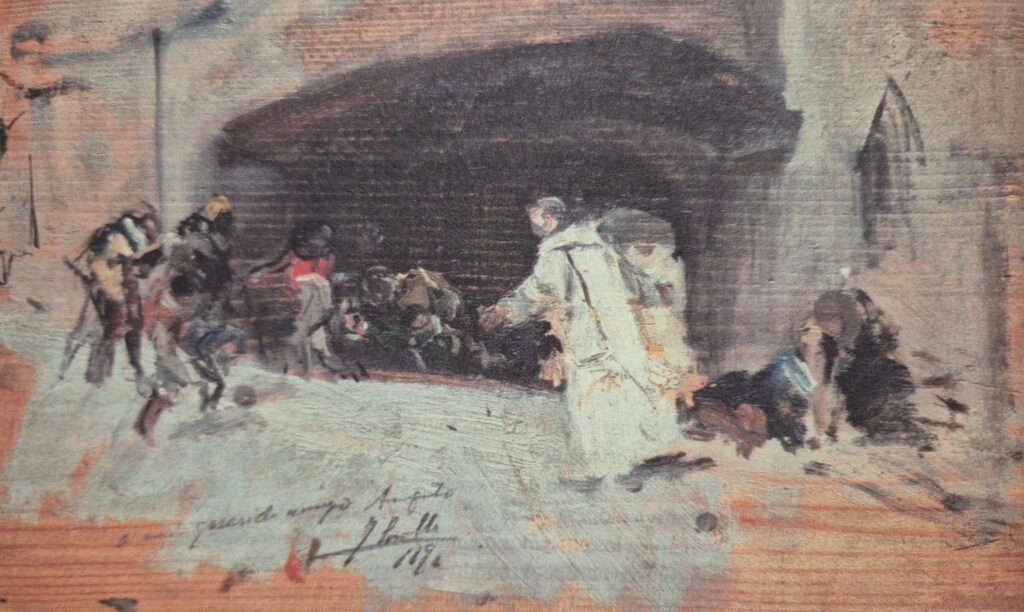

Father Jofré was thinking something along those lines when he saw some guys mistreating a madman in the streets of Valencia in the late 1300s. The famous sketches and paintings of Father Jofré taking pity on the madman and vowing to protect those afflicted by disturbances of the mind, body, and soul, and to have the foresight to provide a location, an actual premise for the poor, sick, and disturbed to find refuge, solace and care. With the support of his parish, Father Jofré convinced the local community and quickly got endorsed by the church to extend his efforts, and so in May 1410 the first mental hospital was built near one of the city gates:

“La edificación del Spital de Ignoscents, Folls e Orats se inició en mayo de 1410, tan solo un ano después de su fundación, en una zona poco urbanizada, perférica y alejada del centro de la ciudad. Para ello se adquirió un terreno plantado de moreras junto a la muralla, cercano al Portal de Torrent, una de la puertas de entrada a la ciudad que con el paso del tiempo se denominaría Portal dels Inocents.” (La nave de los locos, p.119)

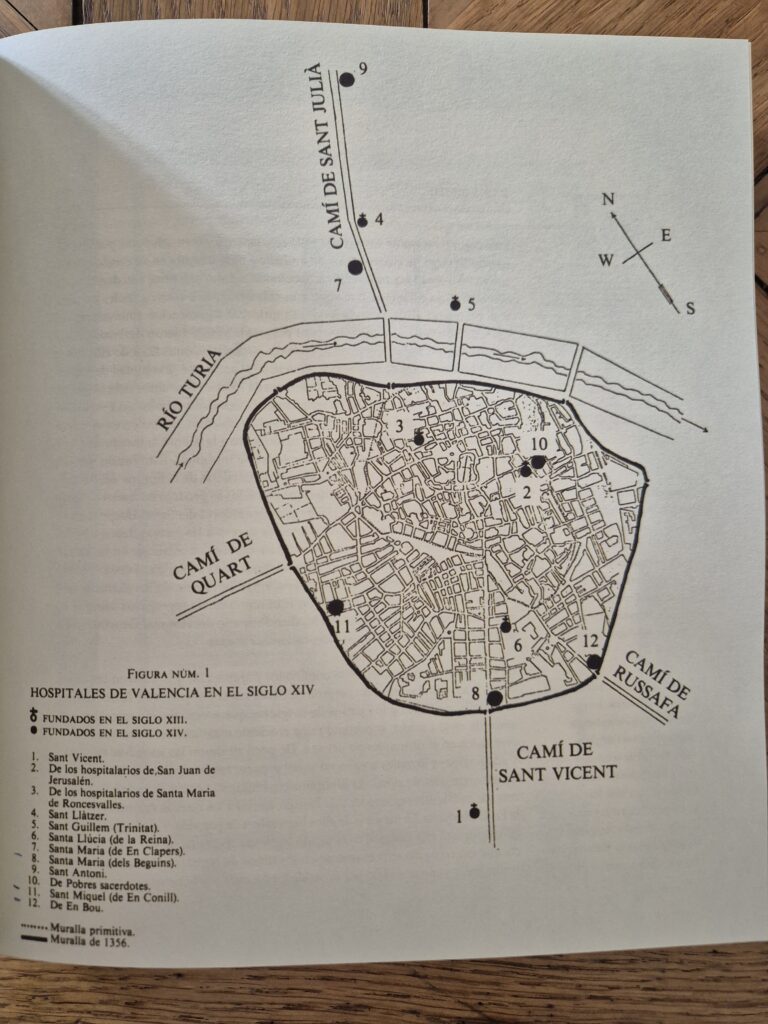

Similar to the orchard garden adjacent to the Maristan of Granada, here at the Folls Spital they were surrounded by mulberry trees. The proximity of nature and the coolness that trees provide with shade and the birds and fruits that always accompany the presence of trees is a recurrent theme. However, it is worth noting that there were other hospitals providing more general care in the growing medieval city of Valencia, such as the Hospital d’En Conill (1399), the Hospital del Beguins (1334), and the Hospital d’En Bou (1399). (La nave, p.120) The originality of the Father Jofré hospital was the specific inclusion of the ‘insane’ as ‘patients’ – although both terms were not in use at that time – and in that sense there is a clear parallelism to the Maristan of Granada that had emerged shortly before in Andalucia. In this shared territorial space of the 1300s, Jofré certainly must have heard about the maristans and their purpose in society.

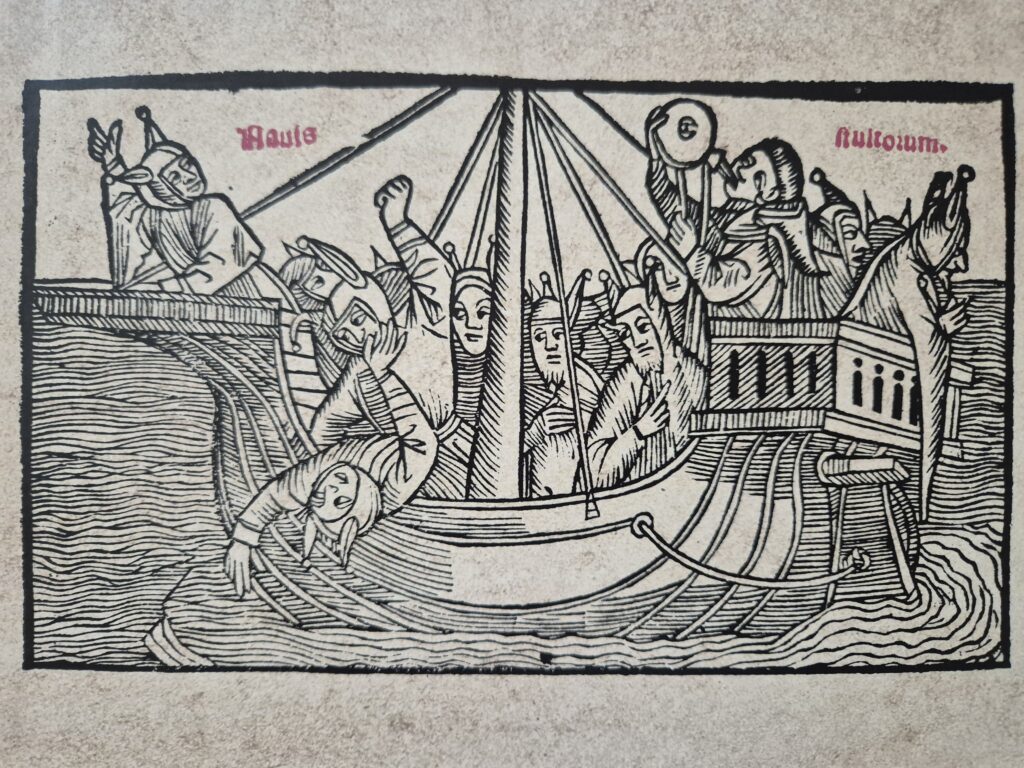

In a chaotic medieval society where the Stultifera Navis – Ship of Fools metaphor is ripe to show the implications of including or following the ‘crazier’ side of humanity, the ship of fools symbolizes the uncertainty of taking such a direction in a tragic-comic sense of steering rudderless into the future and as a sharp critic of those adamant on giving a set direction to a more formalized future that would have foreboding and dire consequences for the variety and creativity and originality of a more diverse society. If normality means conformity, then insanity implies acrimony – this bitter mutual struggle between perhaps wanting and trying to conform but also realizing that the opposition of both is necessary for their definition: normality needs insanity to define itself and therefore repudiates it as it increasingly consolidates and crystallizes the contours of a ‘sane society’ (Erich Fromm, The Sane Society, 1956.)

What to do with the ‘insane’ and all their ‘follies’ then? Here, in the medieval context that you are navigating, the La nave de los locos recognizes the presence and influence of the maristans as places where early medicine and music were used to treat those with mental turbulence:

“Particularmente la música, que ya era empleada por los pitagóricos para reconciliar al individuo con la armonía cósmica, y también por la medicina árabe desde los primeros maristanes, como eficaz recurso para que los internos pudieran sintonizar con la música del alma.” (La nave de los locos, p.261)

Particularly music, which was already used by the Pythagoreans to reconcile the individual with cosmic harmony, and also by Arab medicine since the first maristans, as an effective resource so that inmates could tune in to the music of the soul.

This passage is noteworthy for its recognition of maristans. While the architectural transmission of style and form is not verifiable between the maristan and the modern hospital, however, there is a definite correlation between the geographic proximity of Granada (maristan) and Valencia (mental hospital) in which both are influencing each other, almost mirroring each other in their attempts to gain favor with the population and provide patronage for the caring of the unstable. It could well be that Father Jofré was inspired by the Maristan of Granada or that his initiative occurred entirely in parallel. Given the competing taifas and culture of outdoing the other fiefdom and neighboring rival religion, it is very likely that Jofré in Valencia heard of and indeed was inspired by grand Granada.

Either way, this mirroring effect of developing buildings (care centers / maristans) congruently and institutions (larger hospitals thereafter), occurred during the same time period, only 40 years apart, which implies that there was an osmosis of efforts to care for the sick that local leaders espoused. Under the overarching competing religious banners of Islam or Christianity, local leaders extended and further embedded their influence locally via the establishment of care centers for the unwell, thus gaining the trust and confidence of society. It is important to see these early hospitals as healthy competition between entwined cultures that were vying for predominance within their respective realms. These early forms of institutionalized care were the trailblazers for the modern hospital. In Europe, the Renaissance (14-17th centuries) would usher in a flourishing of the sciences and medicine that would continue to evolve. Whereas the Arab countries would stagnate under the Ottoman Empire for roughly 500 years and then they would be subjugated to European colonialism, including the adoption of its institutional systems such as the modern hospital. In this long hiatus between maristan and modern hospital, it is probable that the maristan inspired the establishment of European care centers in Valencia to include the mentally disturbed, if nothing else, then by hearsay of what was happening with such empathy next door.