Next to another imposing city gate called Bab Zuweila, Ibrahim the caretaker is washing the steps of the Sultan al-Muayyad Shaykh Mosque with a squeegee mop and a bucket of water. He waves you around the wet part and drops the mop to usher you inside. He pushes open the thick wooden doors with the ornate geometric metal designs encrusted in them; the side panels of the arched entrance have La Ila ala Allah (there is no God but God) and Muhammad rasul Allah (Muhammad is His Messenger) in black and white-tiled decorations on either side of the door. You leave your shoes by the entrance and follow Ibrahim into the mausoleum. He chants a Quranic verse that resonates up into the domed ceiling. The marble tomb sits in the middle and knows the answers but says nothing beneath the 8-pointed wooden star frame made of brown beams that hangs from the ceiling. “Dome of the Rock,” Ibrahim says and nods towards a small tomb box: “Ibrahim, the son,” he says. “I thought you were Ibrahim,” you say, and he smiles: “there are two of us here.”

Ibrahim takes you to the courtyard of the mosque and it is truly an impressive view and such a well-kept edifice with green and red rugs covering the stone floor of the main iwan with the mihrab and Qur’ans on display, but there is no maristan. Where is it Ibrahim? He does not know and so you look on your mobile phone where the map had indicated the maristan was located. It’s over by the Sultan Hassan Complex, which is strange that Muayyad did not keep things in the same place. There must be a reason for this that you will need to investigate but now is not the time since every other building on Darb El-Gadid catches your attention as yet another historical monument; another street with no sidewalks except for the old guys sitting on their stoops, here you have one impressive mosque after another. You immediately hit the Mosque of Salih Tala’i and then the Mosque of Abu Heriba, then as the street becomes Al-Tabanaa you walk past the larger Mosque of Amir al-Maridani, and then there is the Beit al-Razzaz that is under renovation with support from the Aga Khan Foundation and the European Union. Here you meet the two Muhammads.

Walking into the courtyard of Beit al-Razzaz is almost like walking into Maktab Anbar in Damascus, except on a smaller scale. Similar to the black and white (ablaq) stripes seen so often, the mashahar stripes of beige and maroon are newly renovated and stand out brightly against the beautiful woodwork and the blue sky above. Situated in the heart of medieval Cairo, this mansion was also built during the prolific Mameluke era. The Muhammad duo explain the ongoing work and show you around the courtyard briefly. Then they point you in the direction of the Sultan Hassan Complex where you hope to find another maristan (they seem amused by your interest in maristans but encourage you nonetheless).

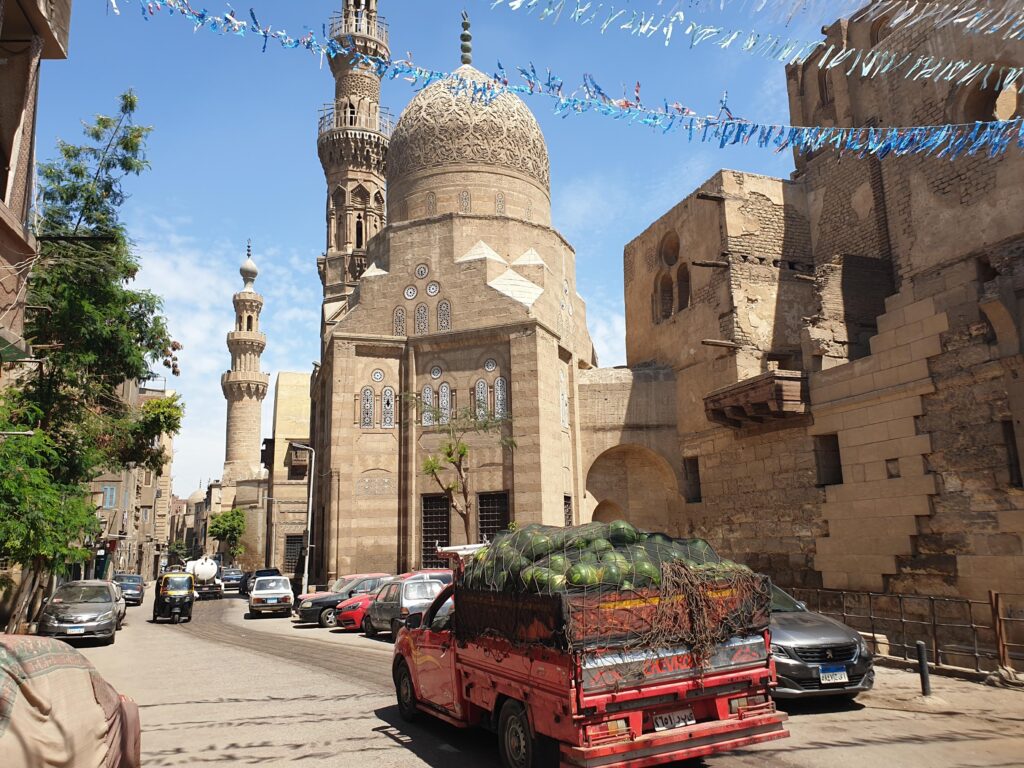

Yalla! Forsa saida, you say and clasp hands, vowing to be in touch for the Maristan Project. You head south down Bab el-Wazir Street, an extension of the same street before with no sidewalks, just stray dogs laying around with flies around them and old men sitting on their plastic chairs on the stoops of their shops: using the V-sign for victory or for indicating to someone to look, they flick their V-shaped finger towards the minarets, motioning for you to look up and to visit their monument. Some young guys putt-putt along in their rickshaws, some ask if you want a ride. You pass the exquisite Amir Aqsunqur Mosque – also known as the Blue Mosque for the unique blue ceramic tiles along the back wall, and then you pass the Umm Al-Sultan Shaaban Mosque and Madrasa. Every corner has another mosque, large or small, it’s impossible to keep track of the sheer proliferation of Islamic buildings.

As you ascend Al Mahgar Street, the past starts to return, you have been here before, in another dream or an extension of the same, the past rushes quickly at you with the derelict shops, the broken road, and then the magnificent façade of the Sultan Muayyad Shaykh maristan suddenly appears around the corner. There are some birds chirping in the trees, some guys loitering in the road, a motorbike honks as it swerves past you. The alley with the broken stalls is in the shade of a massive tree. You cannot recall what house door knocked on to get a photo from their window.

The façade has been restored since you last visited over two decades ago. You are excited to visit and walk around the restored ruins. Two A.S.S.C. security guys with brown and black teeth stop you inside the gate and tell you the customary ‘mamoua’ (it’s forbidden) response as a welcome. You walk past them and take a few snapshots from your phone. They are not amused and tell you to go around the building to see more. The last time you were here in summer 2002 the inside was just rubble and trash. DREAMS was labelled on a small red carboard box. There were large arches and maybe some rafters, definitely no roof, just a gutted-out old skeleton of a building.

Around the back of the Sultan Muayyad Shaykh Maristan there is construction work ongoing. Most of the maristan real estate is being built upon to make new homes for residents. The inside back wall of the maristan is intact and renovated but the rest seems discouraging. The surveyor tells you to go keep around on Labana Street to the other entrance of the maristan. Three young guys greet you and one of them asks for a visa to Europe in return for letting you see inside. His insistence at the end of the quick ‘tour’ proved to not be a joke after all. The sky is much bluer here, you tell him.

Here, they repeat is the ‘nabout’, something about the entrance for the poor and destitute to come get some food and rest. You go inside and find beautifully restored rooms and the 8-pointed star embedded in the wood ventilation window frames. 12 hours per day at 140 EGP, the young guy says. That’s not a lot at all, you agree and he nods towards a restored limestone staircase with a wooden railing, and a courtyard beyond the archway. Mamnoua. The other guy says and you pass under the arche into the courtyard. Mamnoua! They repeat and start to get nervous: they will get in trouble for letting you wander around, they may get fined or fired, so best to not push your luck. That’s enough.

*

There are more hidden surprises on the horizon. Down the road, there is large roundabout that is called the Salah al-Din Square for his Citadel is up on the left. There is probably a maristan in there too, you take note to explore on the next visit to Cairo. For now, you enter the Sultan Hassan Complex – a grandson of Qalawun – who built an even larger mausoleum, mosque, madrasa, and maristan complex. Ahmed at the ticket counter asks for 180 EGP. You say okay, but only if you get to see the maristan. He cannot promise that but he does agree to charge your phone in the little wooden booth. If I cannot see the maristan, I want my money back, you say. Mamoua, he answers and calls his colleague who tells you to go talk with the Administrative Manager in the little office next to the trees down there. A Portuguese lady with sunglasses and a pleasant demeanor buys a ticket while your phone charges, then she disappears into the Rifai Mosque on the right.

At the Administration Office you introduce yourself as politely as possible in your broken Arabic and the lady smiles in amusement at your quest to find maristans in Arab countries. Her name is Hind and she calls her Inspector of Antiquities, Mahmoud, on the phone to come show you the Sultan Al-Hassan Maristan, then she leaves and you will most probably never see her again. Thank you Hind, for making my day. If only all men worked that efficiently. Mahmoud is exceptional as well:

“Welcome, I work for the Ministry of Tourism & Antiquities,” he declares upon arriving in his red-faded hoody sweatshirt that says ‘COURAGE’ in caps on the front with smaller white letters just beneath, confirming: ‘is a decision’. Sharafna, you respond as a greeting code of honor. Up the big stone steps of the mosque you go, take your shoes off, walk on some old green carpets, follow Mahmoud down a somber corridor of ancient stone where a man in a djellaba is sitting barefoot against the wall next to a wooden-barred gate that is locked. Your heart sinks for a moment, but Mahmoud is on a mission now.

“Wait here,” he says but you follow him on more old carpets to the entrance a huge courtyard giving onto massive iwans. To fall for the Oriental cliché: despite the metal scaffolding around the central ablution fountain, this looks like something out of Alf Layla wa Layla (A Thousand and One Nights). Mahmoud calls loudly across the courtyard to the caretaker to bring the keys. Above the sky is blue but somewhat overcast with clouds encroaching on the city. The caretaker arrives and fumbles around with a large chain of keys. He tries one at the padlock of the wooden gate, wrong one; he tries another, no go; the chain clinks and the third key is a fit. “Put your shoes back on,” Mahmoud says as you enter the main corridor to the maristan. Today is your lucky day.

1330 (hijra years) is etched in the cement walls, Mahmoud explains this is when this part of the restoration was done (that would be in 1912 AD). A Hungarian architect by the name of Max Herz is said to have run that show then. There is a curved passageway with individual rooms on either side. The wooden doors are old and broken, inside smells of cat urine and dust. “No one comes here anymore,” Mahmoud says, “we need to renovate the maristan more.” The grandeur of the place implies that the multi-storied edifice could house many people. Mahmoud insists on showing you up some old staircase with no railing with trash obstructing the way. Your hands start to sweat: the angle is perfect for vertigo. You want to ask Mahmoud if you can borrow his sweatshirt.

You hug the wall pathetically and finally get up the stone stairs. Mahmoud is waiting in the somber room, panting, catching his breath. The dust is so thick that it puffs out in little clouds beneath your soft steps. A row of 8-pointed stars in the wooden ventilation frame cuts geometric forms in the cloudy sky behind. You hug the wall going back down again and laugh off the fear of heights with Mahmoud who seems amused. Beneath the maristan is a storage room: cool air is ascending quickly from that basement as if a massive fan were on. Adjacent to the maristan outside was a water well that pumped the water up to a tank that was connected to a canal aqueduct that brought the water into the mosque, madrasa, and maristan. Reminiscent of the hydraulic system of the Romans.

“Here is a room for teaching medicine to students: the maristan was a place for learning as well as treating and curing,” Mahmoud says. You look around the empty square room and that’s pretty much all there is to see. Mahmoud talks about sending some studies about the maristan to give you more information. You are delighted and thank him many times as you walk together towards the exit. When you get to the wooden gate, it’s locked! “You are stuck with me in the maristan!” Mahmoud laughs and goes to the large window in the corridor to call for the caretaker across the courtyard. The same Portuguese lady from the ticket booth happens to be going by the wooden gate that you are holding and asks: “Are you okay?” “Yes, I’m just looking around an old mental hospital,” you say and she looks over your shoulder down the corridor. “There’s not much to see,” you say and she smiles: “Well, good luck getting out.” The caretaker apparently thought that we had already left but Mahmoud thinks he was playing a joke.

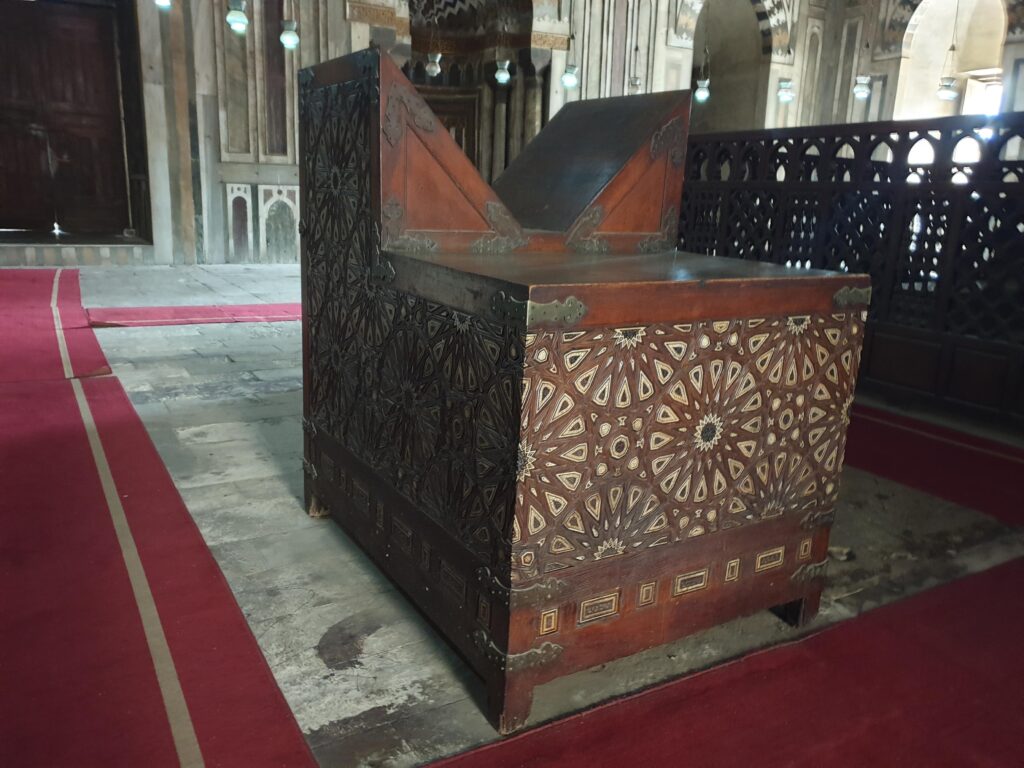

Either way, you say goodbye to Mahmoud and walk across the courtyard to the mausoleum where another caretaker named Massoud sings La ila ala Allah to show the echo percussion of the large room. In the middle of the square are the tombs of Ahmed and Ismael, the sons of Hassan, framed by a single row of old worn red carpet; next to the tombs is a strange mosaic-encrusted wooden box that religious readers would climb up onto to recite from a huge copy of the Qur’an that lay open. Being a good meter and half above ground, the height would allow their voices to carry more easily around the room for the believers.

A frail young man giggles like a girl, then whines weirdly like a colt neighing, and runs with a strange shuffle into a corner of the vault. A lady pursues him but he is too fast and moves around the tombstones, puffing out his cheeks and making blowing sounds, while the fingers of his right hand move quickly, tapping a fast melody that only he can hear. Radwan, the lady pleads under her breath as she tries to keep up with him. They dance around the tombs and the reading box a few times, each time he just barely escapes from her repeated lunges. Finally, the deranged young man calms and she approaches him slowly, whispering soothing words. Yalla, she takes hold of his arm and guides him gently towards the light of the courtyard.

*

Five minutes down Saleeba Street heading west now towards the Nile, on the other side of the street you see the three Turkish ladies that had huddled together and shied away from young crazy Radwan doing his thing in the mausoleum vault. They too are headed to the iconic Ibn Tulun Mosque where a group of students are sitting together on plastic chairs in a circle listening to a teacher speaking. Another group of young women are taking photos by the central ablution dome. The spiral staircase minaret stands stoically and indifferent to the centuries.

The Egyptian chronicler Al-Maqrizi recounts that Ahmed Ibn Tulun had a maristan built next to his famous mosque in AD 873. Like other benefactors who patroned charitable edifices, Ibn Tulun took pride in providing for the destitute and visited his maristan regularly. Once a patient called out to him: ‘Oh Emir, I am not mad as they say, I just want a pomegranate!” Upon hearing these words, Ibn Tulun had a fresh pomegranate brought to the man immediately. Carefully weighing the pomegranate, the man asserted the ripeness of the fruit and then threw it at Ibn Tulun, splattering the red juice and seeds on his white tunic. (Dols, “Insanity”, p.135)

This instance, recorded and transmitted by Al-Maqrizi, is proof for some that maristans existed in the 9th century AD in Muslim lands and that they provided a place for attention to the mentally disturbed. As a footnote to Dols’ analysis, the pomegranate anecdote reveals a potential critique of conditions in the maristan: just as the seeds of the pomegranate are jammed together in the encasement of the fruit, so the maristan may have been overcrowded with the destitute and deranged, thus making care and treatment more difficult, giving the ‘patients’ a yearning for freedom from the place. But this is just conjecture.

The metaphor is a stretch of the imagination: the reality on the ground is that there are no remains of the Ibn Tulun maristan. “Nothing here,” says the caretaker, “but there is the Houd al-Marsoud hospital, that’s old.” He insists so you give him 10 EGP for having watched your shoes while you walked around on the dusty floor. As you walk down the street, the wind picks up and a few raindrops begin to fall on your phone and splatter in the dirt. Down a narrow street with flyers connecting the buildings, people moving at a crossroads, a man selling strawberries, the smell is pungent and permeates the moist air. The rain drops fall harder but sparsely. It’s not really raining, not even drizzling. “The hospital is just around the corner,” says an old man sitting under an awning.

The mustashfa al-qahira al-jildiyya wa at-tanasaliyya (the Cairo Hospital for Dermatology and Venereology) is new enough to have glass sliding doors. Maybe a few decades old, but definitely not from medieval times. Rain drops splatter on the leaves of trees and the hoods of cars and the dusty pavement of the broken road leaving little dark crater spots. You head west towards the Nile: the wind picks up trash and dust, flinging them with the drops through the air. There is a juice shop selling fresh mango, orange, and lemon. A man in a wheelchair is missing a foot. Black charcoal and a pigeon-feather fan on a grill are getting wet.

Scarves are fluttering, clothes are flapping; it’s mid-afternoon shopping time and the girls are looking at clothes while the guys are looking at the girls. There is a boy laughing, dancing in the street with a stray dog on its hind legs standing the same height. A donkey cart with some vegetables on wooden slats passes. A red metal cart carrying three children sits in the road. You are under the overpass now and there is a row of closed green metal stalls each full of books and papers. An old man sits reading the Qur’an in one of them. You walk through the Sayyida Zeinab Metro stop to get to the other side of the tracks: raindrops are hitting you in the face, it’s refreshing; waiting on the curb a man smiles and does not bother wiping his glasses; another man in rags is walking against the traffic towards the river, cars honk and swerve around him.

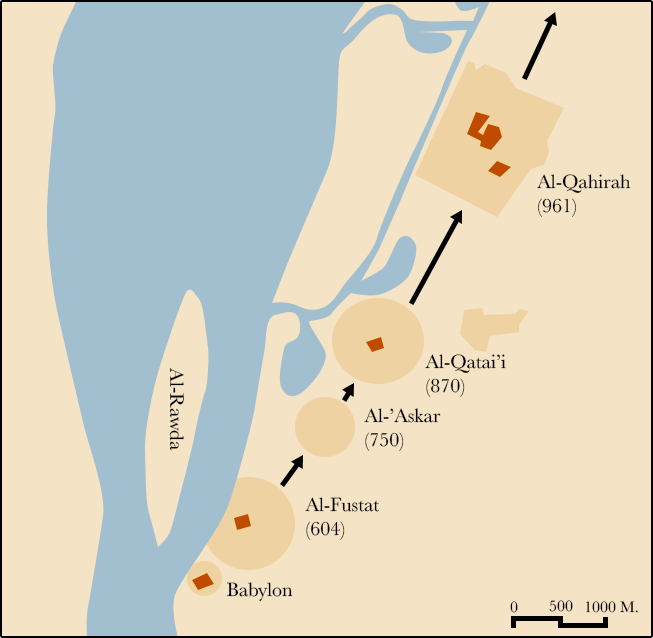

Original map from Nezar Allayad, Cities and Caliphs, fig 5.19.

Across the bridge to Ar-Rawda or Al-Manial Island – the Isle de France of Cairo – you have now walked through part of the four old Cairos that came to form medieval Cairo. In reverse historically, from al-Qāhirah (969) via after the destruction of al-Qatta’i (870) to the replacement of al- ‘Askar (750) to the sacking of al-Fusṭāṭ (604). “Cairo’s boundaries grew to eventually encompass the three earlier capitals of al-Fusṭāṭ, al-Qatta’i and al-‘Askar. Al-Fusṭāṭ itself was then partly destroyed by a vizier-ordered fire that burned from 1168 to 1169, as a defensive measure against the attack.”

With new rampart walls, Sultan Salah Al-Din consolidated these ‘cities’ (now neighborhoods) into one Islamic capital with his Citadel happily protected in the middle. Look at how small these capital cities were, in comparison to the mega-metropolis that has emerged in the 21st century as one of the largest urban sprawls in the world, testifying to the relentless growth of humanity throughout the centuries. In 2024, there are four or five other Cairos forming the mega-city that is the capital of Egypt today with plans to expand further than ever before, bigger than all previous feats, including those of the Pharaohs.

Greater Cairo now includes the centrally-located Giza Governate, the 6th of October City and El Sheikh Zayed City to the west, then there is Heliopolis and Nasr City to the east, and then Al-Oroub City and 10th of Ramadan City to the north-east, and the east New Cairo City and the New Administrative Capital that is President Sisi’s claim to eternal fame: a mega-billion project encroaching into the desert further yet to the east. “Within Greater Cairo lies the largest metropolitan area in Egypt, the largest urban area in Africa, the Middle East, and the Arab world, and the 6th largest metropolitan area in the world.”