Over the mountains east of Beirut, the Beqaa Valley extends below with villages and agricultural fields on either side of the highway heading straight to Syria. In 20 years, the border control station has not changed at all – except that it is easier to cross now. Through the no-man’s-land where transparent blue plastic gallons of green gasoline are sold for $8 per gallon by guys pulled over in the right lane, past the orange earth cut open for the road to pass, to the Syrian border control that has not changed either – except that the faces of Hafez (father) and Bashar (son) Assaad have been torn out of their profile posters next to the ‘Welcome to Syria’ sign above the road. The new Islamist regime wanted to impose an exorbitant entry fee for foreigners of $300 for North Americans, $250 for French and Belgians, $250 for Iraqis, but the decision was not made be whomever makes such decisions in the government now, so after a half-hour of waiting you enter Syria for free.

The streetlamps are askew in the divider of the highway without lanes. There is an unmarked jeep overturned on the shoulder and further down, as the road starts to descend to Damascus, there is a civilian car missing wheels, windshield shattered, just the burned carcass of the vehicle rusting as a reminder of the Syrian civil war that lasted 14 years (2011-2025) leaving the tragedy of over half a million casualties. And the overthrow of 61 years (1963-2024) of brutal military rule by the Baathist Party in December with the unexpected conquest by the Hay’at Tahrir ash-Sham (HTS) of most of Syria. HTS is an offshoot of the Jabhat al-Nusrah (Nusrah Front) that was Al-Qaeda’s former branch in Syria. The main cities of Aleppo, Homs, and Damascus fell quickly to HTS, as Israel moved into southern Syria (and as far north as Quneitra) and occupied the Golan Heights in the process. Ahmed al-Shar’aa, the HTS leader, proclaimed freedom to Syria and changed his military uniform to coat and tie; he even wears a Philippe Patel watch. HTS encourages women to wear the niqab. Revenge killings against the Alawites in western Syria will come in March 2025.

Descending the road to Damascus at night, you would have seen the green lights of minarets sprinkled across the city like glimmering emeralds. But there is no electricity now, only individual oil-powered generators, providing energy to stores and homes. No need to mention in detail the middle-man black market that has emerged. Gasoline comes in mainly from Lebanon. The currency exploded during the civil war with x100 inflation rates reaching somewhere between 9,000-10,000 Syrian pounds to the US dollar. In Lebanon, it’s even worse: the Lebanese pound unpegged itself from the USD at some point and floated upwards into x60 inflation rates at roughly 90,000 Lebanese pounds to the USD. Everyone is a ‘millionaire’ in Beirut and everyone accepts USD too so it’s a parallel currency that is difficult to comprehend. And everyone in Damascus carries around wads of cash that they flip through to pay for things. There are no credit cards in Syria; there are no ATMs. There is still a civil police force of around 500 guys waving at traffic in Damascus – they get a salary of 170-180 USD per month – when they get paid.

*

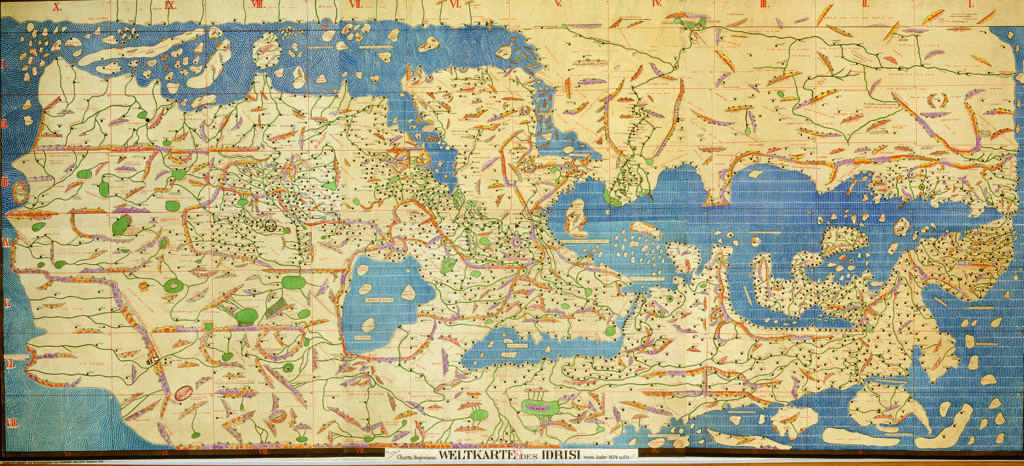

In the heart of the old city of Damascus – one of the oldest inhabited cities in the world – “time is stopped”, Farouk Saies says, as he looks around the courtyard of the Maristan Nour Al-Din (‘Light of God’) Zangui, commonly known as ‘bimaristan an-nouri’. The great steel doors are open and the inner wooden doors, also studded with metal pegs, have also been opened, giving onto a beautiful square courtyard with a central pool that is full of floating and rotting naranj(a bigger more bitter form of orange). In the corners of the courtyard, there are large jasmine plants growing towards the roof and hanging down in clumps. In the spring, the air is filled with the scent of jasmine and the citrus trees. There are also side rooms that used to be for patients, long since converted into display cases for ophthalmology, medicine, blood-letting, pharmacology, plants and herbs. The electricity is out. Behind a smudged pane of glass, you see Muhammad Idrisi’s ‘upside down’ map of the world:

Farouk tells you a similar story that you read in a history book regarding the bimaristans in Baghdad: the leaders asked the physicians to hang meat in different locations around the city to see where it rotted the least, and in those locations the hospitals would be built because the air was cleanest there. The air is fresh and the blue sky is clear. Farouk is shifting his weight and rubbing his hands from the cold. You take some more photos to document this visit. Parts of the maristan have clearly been restored since the turn of the 21st century: the diwan arch and its side panels, the pair of peacocks above the inner wooden doors, and the marble work of the smaller side diwans with geometric mosaics. The French most probably restored the brick cupola and added those glass bubbles as well as the muqarna above the entrance. All the captions in the display rooms are in Arabic and French still, some are hand-written.

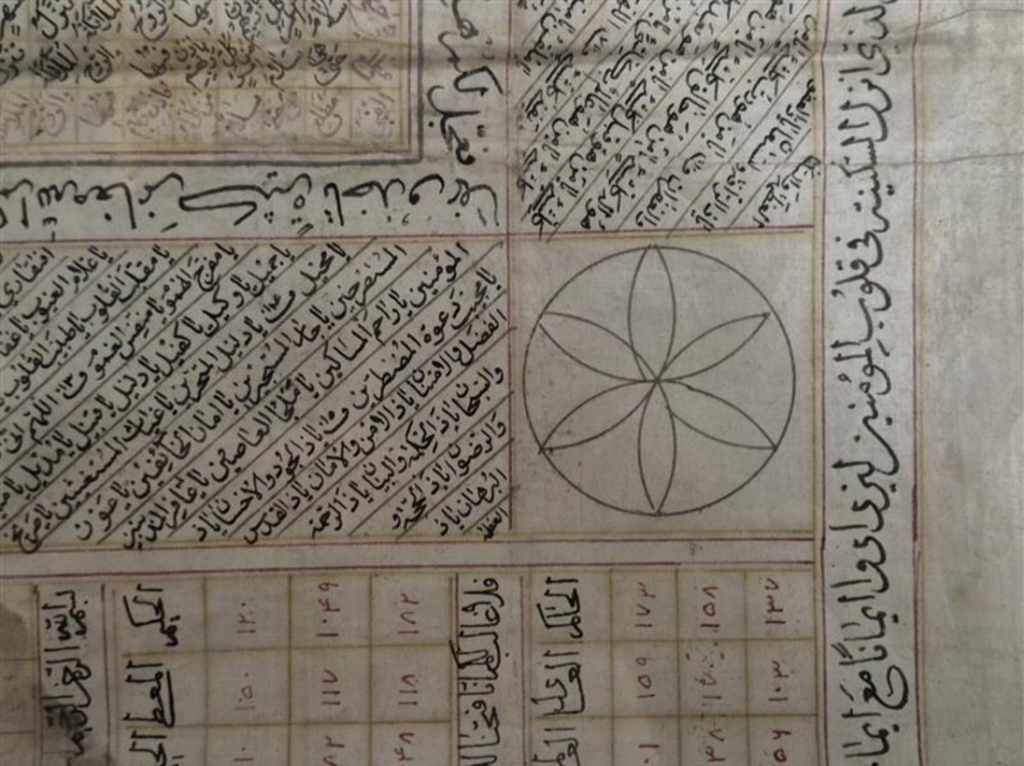

As you enter the maristan, there is an identical old metal scale hanging on either side, next to identical amphora that could be Roman – there are plenty of Roman columns embedded in architectural structures around the old city of Damascus. The scales are large flat squares attached to chains and a metal shaft and balance system for weighing products such as powders, rations, and patients perhaps. Inside one of the display rooms, there is a garment, just like the one you saw in the Egyptian Islamic Museum, the ‘red chemise’ that is covered in verses from the Quran. Medieval Muslims believed that if the medical cures of the times (plants, herbs, music, water) did not assuage the malady, then the patient should wear this jacket and pay particular attention to the ‘Ayat Al-Shifa’ (the curative verses) in order to seek solace from above. There is a perfect circle with the imperfect petals of a six-pointed star on this camise.

Hanging on a wall in another display room, there is a remarkable door that is ajami woodwork. The ajami floral style is definitely Persian and can be found in many old Ottoman palaces and houses around the old city of Damascus, but it was most probably not an original from the Maristan al-Nouri of the 12th century. This maristan has become less about a ‘place for the sick’ and more a French ‘Musée de la médecine et des sciences arabes’ as the plaque says outside the main entrance. Here, you will find a short description of Ibn Al-Nafis, the damascene polymath physician, who discovered blood circulation in the 13th century, long before the British doctor, William Harvey (1578-1657). You will find a note about Ali Ibn Isa al-Kahhal, the great ‘oculist’ ophthalmologist of the 11th century who treated cornea and iris maladies, long before modern medicine. And Ismail Al-Jazari is there too: you will learn about the great inventor and engineer of the 12-13th century who designed the fantastical ‘elephant clock’ you saw in the Cairo Islamic Museum too, and who designed the noria (water wheels) that would become so influential.

*

In the maristan courtyard, there is a small replica of a noria that is strangely out of place. The pool is not working due to the lack of electricity. Farouk needs to get back to his work at the Syrian Ministry of Antiquities and Museums. You do not hear the music or the sound of water that treated the sick here. There is a caretaker sitting against the wall in the sun flipping through posts on her mobile phone. The other caretakers are clustered together by the box office at the entrance. You follow Farouk through the cold alleys of stone and shops filled with spices, fruits, food stands, people talking and buying, others just going somewhere too. There are shafts of light coming through the holes in the metal-arched roof covering the street. They say the holes are from French bullets when France withdrew from Syria in 1946 or maybe when the French conquered Damascus on 24 July 1920. The shafts of light that people walk through leave big coins on the ground. In the Souq al-Buzuriyyeh, you pass the Hammam Nour al-Din where you went so often in the evenings to get a shave, to wash in the baths, and have tea after, and then you enter the largest caravanserai of Damascus, covering 2,500 square meters, in search of a book about the bimaristan.

Inside the Khan Asad Pasha al-Azm (1751-1752), the courtyard opens upwards into a colossal vault supported by four massive pillars of zebra-striped ablaq (black-and-white) stones. There is a small café tucked to the right and chairs with purple cushions. A few young couples huddle together in the cold of this open-air refrigerator. The boys smoke cigarettes and sip coffee; the ladies drink tea and wear sunglasses. In a small room on the right, Farouk finds Mohammed behind his desk in the dark, except for a small electric lamp that sheds a neon glow across the pages of an open registry book. Mohammed has a limp in his right leg that is slightly deformed. He pushes open a wooden door and disappears into the darkness. After a few minutes, he emerges and hands over a thin Arabic book about the “Bimaristan Nour al-Din” to Farouk who gives it to you for free. Mohammed refuses to take any money for the book and wobbles back behind his desk. Farouk leaves for work and you hear Fairouz singing softly from a corner in the courtyard: habaytak bil-shitii… (I loved you in the winter…) habaytak bil-saif… (I loved you in the summer…).

Outside of the entrance of Souq al-Hamidiyyeh, the young policeman is waving and whistling at the cars; he is the master of the crossroads, directing an orchestra of honking vehicles that are emitting grayish fumes, tinging the air with an acrid odor. You see the statue of Salah al-Din on his horse looking past them all towards the clear blue sky. The wind is cold; the sun is strong. The light is warm; the shade is cool. Contrasts are accentuated by the winter. You see grey clouds above the hills, painted with golden edges. You are driving back to Beirut and see electric wires shining brightly from pole to pole, making silver snakes along the side road climbing into Lebanon. Bright stencils of people crossing the street of a village, the last light creating haloes around their figures. You see snow falling now on the low mountains (-7 degrees Celsius) and thick snowbanks along the roads. Then descending the hills amongst Mediterranean pines, like skinny broccoli, with white confetti caught in their needles, you see terracotta rooftops appearing in the valley. Suddenly the buildings of Beirut are spreading out below, falling almost into the sea, and the splotch of pink sun squished below the dark clouds on the horizon.