When you type ‘maristan granada’ into a quick Google search, you do not expect so much information to pop up on your mobile phone screen. Twenty years ago, you had visited Granada when the maristan was in ruins. You had knocked on doors in the side streets around the maristan; no one had answered. Some guy sitting in the sun on his little balcony was getting his hair cut by his girlfriend. You had called up to them: he seemed amused and let you come up to take some photos of the archaeological remains below with your little disposable wind-up Kodak. You had tracked down the location via some old maps and found the architectural sketches by the renowned Spanish architect Leopoldo Torres Balbás (born and died in Madrid, 1888-1960) who became head custodian of the Alhambra Generalife compound. You walked around the medieval Albaicín neighborhood until you found Calle Bañuelo where the hammam (public bathes) were located as well, adjacent to the maristan, purposefully so – as you would learn later.

Twenty years ago, you had identified maristans in Aleppo, Damascus, Cairo, Fez, then you had dropped your research on Baghdad, Jerusalem, Tunisia, Turkey, and Iran when you were sidetracked with the realities of life, and by other projects, people, and places; but now looking at the screen on your cellphone, you rejoice to see that the Maristan de Granada is now a tourist attraction: one of many renovated historical sites in Albaicín open to the public for visiting hours between 9am and 2:30pm and then from 5pm and 8:30pm. Keeping in mind the timeless siesta in mid-afternoon, the next morning you leave early and drive fast for half-an-hour from the Mediterranean coast south of Motril next to Salobreña and its white hilltop castle, almost straight north, up to the former Nasrid stronghold of Granada; based on a tip from a friend, you find the free parking lot under Hotel San Antón, 74 c/San Antón, not far from the Roman bridge; and then you go on foot through the streets to find the maristan.

For 7.42 euros a person (as of time of the visit in 2023), you can get a daily ticket to see multiple restored or partially restored cultural heritage sites (the famous Monumentos Andalusies) around Albaicín, including the Palacio de Har al Horra: residencia oficial de Aixa la -Horra, madre del último emir granadino, Boabdil; Corral del carbón: la alhóndiga de los mercaderes; Bañuelo: uno de los baños árabes públicos mejor conservados de la peninsula; Maristán: Fundado como hospital por el sultán Muhammad V en el siglo XIV; and the Casa Morisca (c/ Horno de Oro). This is truly a fantastic tour of previously inaccessible buildings in the old medieval city of Granada beneath the royal Nasrid castle – the majestic Alhambra (the ‘Red One’ in Arabic for the warm earthy red colors its bricks exude at sunset). Bordering the River Darro that cuts through the gorge beneath the Alhambra, Albaicín is a maze of cobblestone streets weaving back and forth up the hillside, leading to mirador vista points near the top where tourists congregate to take photos and gaze at the afternoon sunrays warming the defensive walls of the fortress that looks out across the valley beyond.

Photo: Stuart Reigeluth

From the Sierra Nevada mountains, the medieval Muslims built great networks of canals called acequias that use gravity and the slopes and reservoir basins for transporting fresh water to the Alhambra and the Albaicin. Today, the remnants of some 400 kilometers of acequias can still been found in the Sierras around Granada and even within the city – not far from the Hotel San Antón parking lot – you can see plaques stating where the acequias arrived in the city. Further up in the Alhambra, the same pressure of gravity would create the hydraulic force to spray little shoots of water from the mouths of lion statues in the famous Patio de los Leones. The Arabs inherited and enhanced the usage of gravity for moving water from the Romans. The historical and scientific osmosis remains tangible today. (The rather simple community-operated watercourse technology would be transmitted from Spain to its colonies in South America and make its way into Mexico and South-West USA where remnants are also found today.)

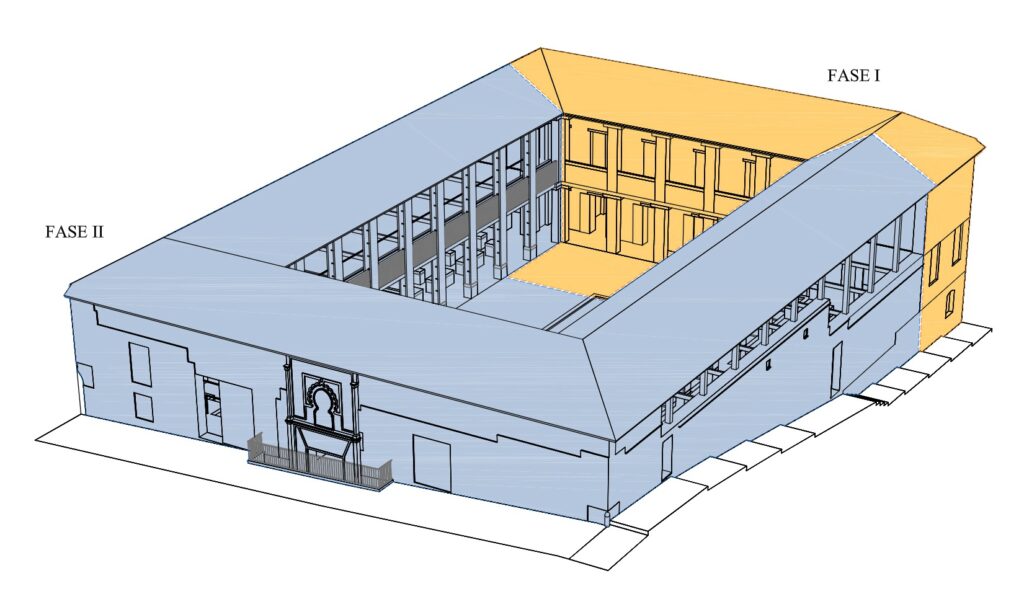

Down below, by the river, as you turn into Calle Bañuelo you can go into an old hammam on the left and walk around the empty rooms with the geometric star-configurations cut out in the stone ceilings for light to come in here, where locals used to hang out in the steam to wash and converse. The hammam was placed strategically near the hospital for easy access for patients and locals. Then as you ascend the street, there is a modest entrance on the right that gives onto the courtyard of the Maristan de Granada. The main entrance to the hospital was on the southern side, the plaque of whichcan be found in the Museum of the Alhambra on the ground floor of the Palace of Carlos V in the Generalife. Phase 1 of the restoration (2017-2022) includes a reception area, a fake glass pieces emulating a pool of water somehow, plus informative exhibition panels in different rooms that give many details and images of what the maristan may have been like. You ask the young receptionist for the contact details of the great Andalusian architect, Pedro Salmerón Escobar, and his colleagues who curated the exhibition: she looks up from her cellphone and tells you with smile to go see if you can find it in the exhibition.

Source: Pedro Salmerón

This was over one hundred years before the fall of Alhambra to the Catholic Kings in 1492 – the same year the same kings sponsored Colombus’ trip to ‘discover’ the Americas; over one hundred years before the maristan would be converted in 1497 into the Real Casa de la Moneda where the minting of money was made until 1685; before it became a Casa de Vinos in 1748 when some friars of the barefoot order of the Convent of Belen sold the building to a wine merchant who used it as a storage space; before becoming a prison in 1825 for convicts that caused a fire in 1834 that destroyed a large section of the edifice; and then it became a local social housing complex for the poor – going back somewhat to its original purpose with a rather destitute spin – until it fell into disrepair in the 19th and 20th centuries with numerous sections being destroyed completely.

You look up ‘librerias’ on your phone and go in search of books about the ‘maristans’ and the 700-year Arab-Muslim presence in Andalucia (southern Spain). After visiting a couple of little bookstores down different side streets, you come upon the Liberia Babel on Calle San Juan de Dios, across from the Real Monasterio de San Jerónimo and some Universidad de Granada faculties. You ask about mandrakes for a parallel project and about maristans and medieval history. The lady behind the counter convinces you to get a copy of Mandrágora by Laura Gallego who is a best-selling Spanish author for children and young adult books (it’s a great read!) and then an older salesman starts pulling out different historical fiction books by Jesús Sánchez Adalid that are popular: Las Armas de la Luz (2021), El Mozárabe trilogy, Los Baños del Pozo Azul (2018) all about the Caliphate of Cordoba. These are all bricks and probably do not mention maristans. And then the revelation:

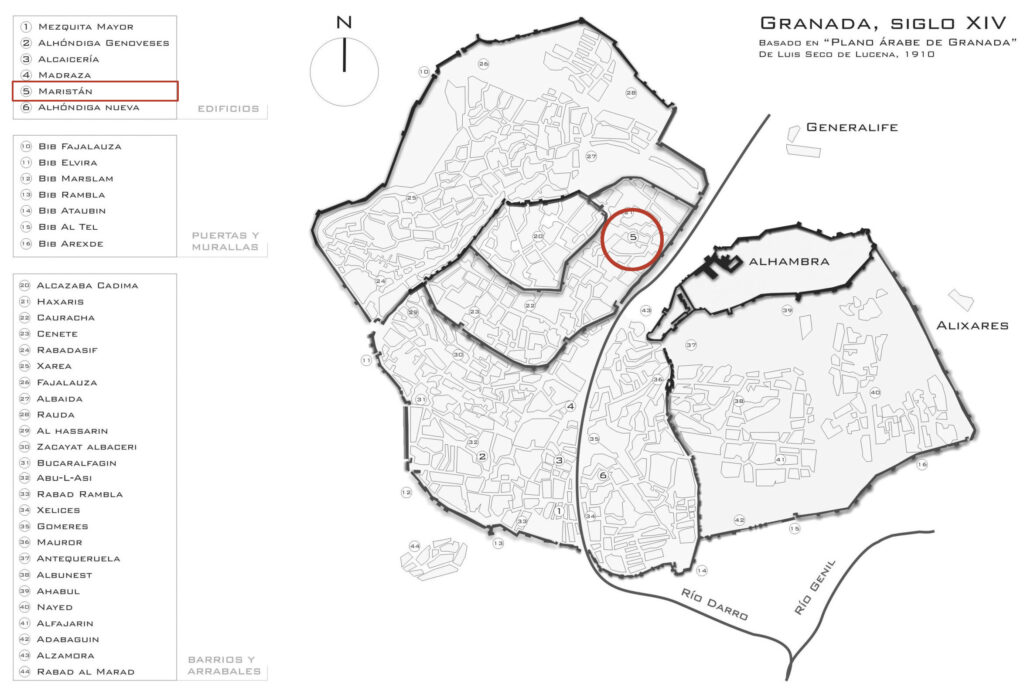

A local gem called El perfume de bergamota (2007, 5th edition 2020) by José Luis Gastón MorataE – a doctor himself and author of numerous books including La Muladí. Granada 1475-1500 (2012) amongst others. You open the book and the first sentences refer to the maristan [Hamet acababa de llegar a su casa. El corto trayecto existente entre el Maristan y su Vivienda lo habia hecho … page 11] and as you flip to the back you come upon an old Arabic map redesigned for the contemporary viewer and there is the maristan highlighted near the Alhambra in the Albaicín neighborhood. This is a historical suspense novel about the poisoning of one of the last Muslim emirs of the Nasrid dynasty, told via the narration of the main character, the maristan physician. This will launch you on reading The Physician (1986) by Noah Gordon that also includes a whole section on the maristan in Persia. As you get into reading El perfume de bergamota you decide to translate it to English. The next week, with the help of some Spanish colleagues, you have talked with his publisher from Almuzara and things are starting to move.

Source: José Luis Gastón Morata, El perfume de bergamota (Granada: Almuzara, 2020, 5th edition).