Over the course of June and into July, you had embarked on translating El perfume de bergamota in Almeria and had sent exploratory emails around to find Pedro Salmerón. You had been called back to Andalusia for a parallel project. No one had responded to your emails, and the weeks passed, until a response came from Rosa Perez de la Torre who is a researcher linked to the restoration of the Maristan de Granada. She would become a constant source of support and inspiration, inviting you for lunch at her place in Granada with her partner, another reputed architect Juan Manuel Zamora Malagón and feeding you incredible academic sources like Cuardernos de Alhambra that have numerous longer features about different aspects of science, medicine, architecture related to the Maristan de Granada, plus other more general publications like Alhondiga (a local bi-monthly magazine) that published an article by Pedro Salmerón about the maristan. The search for maristans was relaunched! Rosa called Pedro who had gone into (semi)-retirement and explained the situation. He agreed to meet the next day in Granada.

“Se puede afirmar que se trata de una estructura dotada de un magnetismo especial, de un atractivo sutil, si se piensa como objeto arquitectonico con una geometria decidida en el entramado urbano medieval, poseedora de una fuga de tipo perspectivo que senala a la fortificacion de la Alhambra, cuyuos bastions se alzan en picado en una bellisima vista que crea un fondo dominante.”

This is a structure bestowed with a special magnetism, with a subtle attractiveness, if one thinks of [the maristan] as a an architectural object with a determined geometry set in the medieval urban patchwork, providing a perspective of flight towards the fortifications of the Alhambra, the bastions of which swoop upwards creating a beautiful view of this dominating backdrop.]

“El maristán nazarí de Granada. Recuperación de un monumento en una difícil encrucijada / The Nasrid Maristan of Granada. Restoration of a monument at a difficult crossroads.” Cuaderno de la Alhambra. 2020. #49. p. 82.

Many years of searching and researching were coming together: you describe this project that would connect the different maristans from Spain across North Africa into Middle East, retracing the expansion of Islam and the transmission of knowledge, science, and architecture in reverse, from West to East, with an exhibition, a book, a blog and so on. Pedro smiles and sips his espresso: he is retired but he’s still involved in the restoration of the Maristan de Granada. His team of architects and researchers won the bid for the implementation of the first phase (2017-2022), and they won the follow-up bid for Phase 2 which includes the remainder of the maristan. He opens the Alhondiga magazine and flips to his article to show the visuals that depict what the maristan could have looked like.

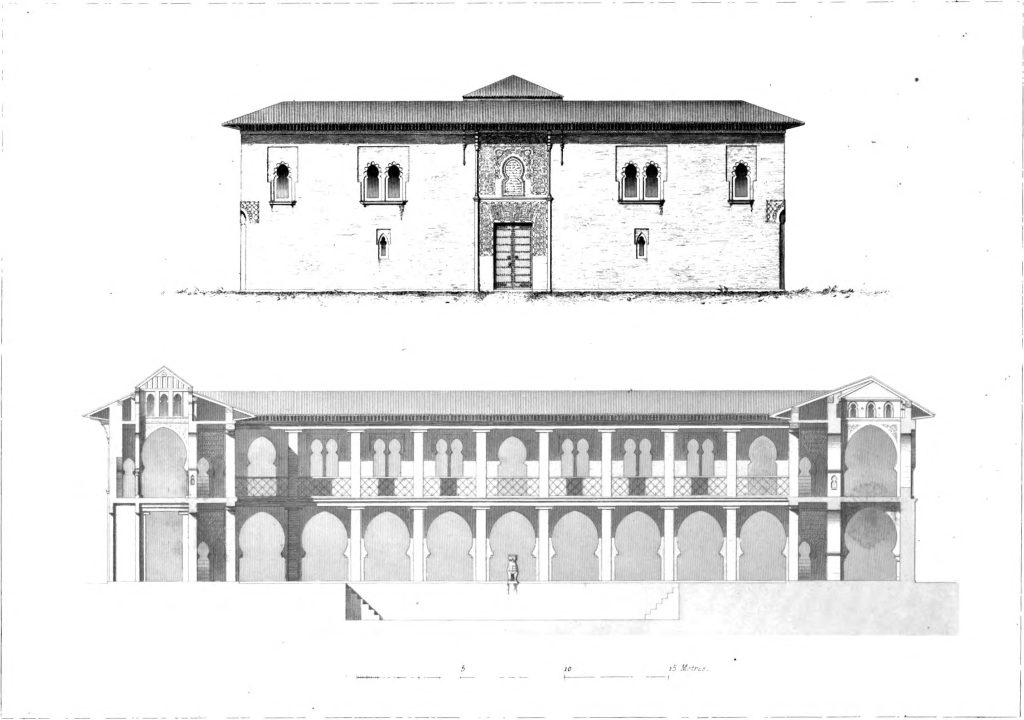

You realize that these are the top experts in the world on the Maristan de Granada. They know every detail inside out. They had identified a discrepancy in previous architectural plans that showed the erroneous location of the staircases in the corners of the buildings rather than towards the center of the long sides of building behind the central location of the lions. Given their excavations, they had irrefutable proof that the designs by Francisco Enriquez ‘Planta del Hospital Arabe de Granada’ in Hospital Arabe a Grenade (1858) by some French editors were not correct. (See ‘El maristan nazari de Granada. Recuperacion de un monumento en una dificil encrucijada.’ Cuadernos de Alhambra, Issue #49, December 2000, page 77.).

Listed in 1981 as a Monumento Arquelogico, the maristan suffered and endured a parallel process of demolition of the crumbling walls and excavations of its foundation that started officially in 1983 when a technical team was deployed under the guidance of the Comision de Patrimonio Historico and the Museo Arquelogico de Granada. The beautiful southern entrance portico was salvaged in 1986 and sent to the Museum in the Alhambra for preservation and tourist visits where it remains today – with the potential for reinsertion with Phase 2 of the renovation under discussion in 2023. In 2005, the maristan was officially labeled a historical monument that once housed and took care of 200 people at a time, according to the account of the doctor-turned-novelist Jose Luis Gaston Morata in El perfume de bergamota (p.73) and confirmed with a nod by the grand specialist Pedro Salmerón.

“Water always makes different sounds, depending on the height of the fall or the depth of the descent – depending on your perspective and location: water has different sounds,” Pedro says as the former lead architect for the restoration of the Patio de los Leones in the Alhambra precinct. How is it possible for water to arrive from the mountains via the acequias (water canals) and provide enough pressure to give these magnificent little fountains enough power to piss melodiously into the pool of the Lion’s Court?

Pedro smiles and says “gravity”, then he extrapolates on a tangent about the hydraulic powers of canals that literally channel the force of gravity into rivulets and smaller stone dispensers (surtidores de agua) that create enough force to exit the faucets into pools giving that lovely fountain effect. This is all just simply physics from the Romans and their aqueducts: understanding and coupling the tremendous force of gravity with the insistence of liquid movement to project sprays of water into basins for humans to admire. If you want to learn more about how the famous lions of the maristan spewed water in the 14th century, you should read Pedro Salmeron’s essay in special edition of the Cuadernos de Alhambra about the Lion Fountains on the patio of the Alhambra that will give an engineering genius a head rush at the ingenuity of using stone and water to make music.

Pedro is a man dedicated to his trade, who has given his life to the study of architecture and to the restoration of buildings for others to see and understand what the past gave to the present. He describes the “gorronera” in the door frames that were found during excavation: these are obvious giveaways of thresholds as they are holes chiseled in the stones to insert the wooden or metal poles connected to the wooden or metal doors, most often it was wooden shafts with a metal wrapping to enable for smooth sliding when pushing the door open or closed. You saw these same ‘gorroneras’ with Naim Zabita – the architect of the restoration of the Old City of Damascus – when you visited the Citadel of Aleppo and he showed you the proof in the whittled limestone. The small holes in the stone were found in the Maristan de Granada, just as in the architectural buildings of the Levant, including the famous Citadel of Aleppo and its Maristan of Nour al-Din. This is not a coincidence; this is an architectural technique that transcended geography since it was simply a way of inserting doors into building structures. This could be compared to inserting windows into frames as a means for seeing out, so it is hard to say that doors and windows are proofs of concept of civilizational osmosis. One thing is for sure: being part of the same world in historical time and geographic space, there was an osmosis of knowledge that enabled the transmission of such techniques to permeate different territories.

Rosa points across the street at the Basilica and explains how this building was previously a hospital that had adopted the open-ward style of treatment that was reflected in the large long knaves, contrary to the more personalized individual approach of the smaller rooms in the maristan. Rosa had just come back from a trip to Fez (spring 2023) where she had visited the maristan there with her friends. Pedro mentions the water clock (clepsydra) in Dar al-Magana in Fez that you visited once long ago, but he seems to have a special penchant for the orchard because he goes back to that again and describes the possibility of opening the view of the maristan onto the Alhambra more and connecting it was the Darro River walkway. He talks about the ventilation quality of the maristan structure and the light and echoing Michel Foucault’s mention of the maristan in his Histoire de la folie a l’age classique (1972):

“En tout cas, ce n’est peut-etre pas un hazard si les premiers hopitaux d’insenses en Europe ont ete precisement fondes vers le debut du XVe siècle en Espagne.”

In any case, it is probably not by chance that the first mental asylums in Europe were founded precisely towards the beginning of the 15th century in Spain.

Michel Foucault, Histoire de la folie à l’âge classique, Paris: Gallimard, 1972, pp. 159-160.

Pedro describes the maristan as a place for the poor and sick to have safety and treatment, the edifice is a vessel acting as and symbolizing a tangible bridge between different eras of our shared history from the Middle Ages to modern times. Rosa agrees but adds the nuance that nothing is so linear. “Go visit Hadrian’s Villa“, if you get the chance, she encourages you: there you will see a parallel form of the hospitalia that had emerged and would also influence our Mediterranean world.

After saying goodbye to Pedro and Rosa, you head over to the Alhambra to find the lion fountainhead that was originally in the maristan, now in the Museum of the Alhambra. From Albaicin, you walk up and cross the Darro River going past a new Hammam that is also advertised on the back of the same Alhondiga magazine that Rosa gave you. Then you ascend the Cuesta del Rey Chico which is a steep incline ascending almost a kilometer long and elevating nearly 100 meters. The slope was named after the last Nasrid sultan – Boabdil – who took this route to lead a rebellion against his father Sultan Mulay Hacen (the highest peak in the Sierras is named after Mulay Hacen) or so the legend goes. The slope was also named Cuesta de los Molinos given that it is near acequias and watermills. Towards the top of the path, you read about the other names of the slope that are less interesting, and on a faded marron red stone wall there is a poem by Federico Garcia Lorca commemorating his 100th birthday in June 1998:

| quiero bajar al pozo | I want to go down to the well | |

| quiero subir los muros de Granada | I want to climb the walls of Granada | |

| para mirar el corazon pasado | to look at the heart pierced | |

| por el punzon oscuro de las aguas. | by the dark hole of the waters |

The sun is beating down and there is no shade: just the red walls of the Alhambra and the dirt pebble path. Separating the Generalife administrative buildings to the left, you can enter the Alhambra precinct for free and visit the Museum where you will find the room with the majestic lion – much larger than the smaller replicas that stand in a defensive circle on the Patio of the Lions – this is one of the original two lions that were at the maristan. On the opposite corner of the display room there are pieces of water dispensers (surtidores de aguas) in a plexiglass case and mounted on the adjacent wall there is the beautiful plaque that decorated the southern wall keystone entrance of the maristan.

In the Museum shop, you peruse the books and see a stack of copies of El perfume de bergamota next to Tariq Ali’s In the Shadow of the Pomegranate Tree. You ask the sales lady for other recommendations since you’ve read Tariq Ali’s and translating Gaston Morata’s book. She seemed surprised and hands you a bilingual copy of Ibn Zaydun’s Casidas Selectas in Spanish and Arabic. This will be good practice you smile and she gives you Antonio Gala’s El Manuscrito Carmesi (1990) that is a fictional memoir written in the first person as Boabdil – the last Nasrid caliph – fleeing Granada from the Christians to find refuge in Fez, Morocco, where he will die alone. You will walk out with your books, past the hordes of tourists, down a different long winding road in the shade of big branches with bright green leaves creating a cool tunnel of trees on either side. On either side of the asphalt road, there are little water canals that flow down towards the Darro River.

In your flight back north, you will plow through the El manuscrito carmesi and you will realize that the central role of the maristan in medieval society is no fabrication of the mind but rather a reality that has been passed on through the generations so that contemporary 20th century writers like Antonio Gala use the term easily, almost flippantly, in this case in the words of the old gardener (former military soldier) who is explaining who much work he has to do in the Alhambra garden during Boabdil’s last reign:

“En junio y julio pasan tantas cosas que no podria enumerartelas aunque no callase en mi vida. Hay tanto por hacer, que nos volvemos tarumba y nos tienen que llevar al maristan; la siega y la trilla son una siesta, no te digo mas.”

In June and July, so many things happen that I could not list them all even if it were never quiet again in my life. There is so much to do that we go loopy and they have to take us to the maristan; the harvest and the threshing are a siesta, I can’t tell you more.

Antonio Gala, El manuscrito carmesí, Barcelona: Editorial Planeta 2023, 1990, pp. 57-58.

‘Take us to the maristan’ – a common reference for the madhouse or mental asylum where the disturbed go to get some rest and balance with the treatment of water and shade and music. In Cairo, there is a neighborhood that is known as the maristan and if you say something that is a bit ‘crazy’ or off beat people will tell you jokingly to ‘go visit the maristan’. That’s where you are headed on this journey: to go visit some more maristans around the Mediterranean!