In the early evening, you go for walk to find the first hospital in Valencia, possibly in Europe. The streets are lined by big plane trees with large leaves that provide shade and dappled shadows on the sidewalk. You arrive at the University of Valencia Faculty of Medicine next to the Clinic Hospital. The receptionist looks completely lost when you ask her whether she knows about monk Juan-Gilberto Jofre and the first institution he helped found that is supposedly laying beneath this building. “INFORMACIÓN” is written in big letters on the glass partition of their office. Another lady pipes up and does a search on Google finding something on Wikipedia but first she prefers to tell the story of when she was a little girl and her grandfather was here in the hospital next door and she would wave to him from the shade of the poplar on the sidewalk. She smiles at the thought of her grandfather and then goes back to telling you that Wikipedia says the Jofre Hospital of the Poor and Innocents that was built in 1409 was actually over where the General Hospital of Valencia is, some kilometers away. The receptionist says you can take the bus and that it’s not so bad, it should only take about an hour. You smile and the other granddaughter lady says there is nothing here to see, and everyone is in exams now so no teachers are going to see you. You’re not sure that professors take exams but anyways the dead end of becoming evident.

Outside the temperature is a sweet 25 degree Celsius with a pleasant evening breeze passing through the streets. You walk along the gardens in the dappled shadows of plane trees. There are also jacaranda trees with their surprising purple leaves and their scrunchy seed pods. You want to reach up and pick some of the pods but they are too high. You would need a ladder and there are no ladders. Just some wooden benches along the dusty dirt path. You can’t really climb on the bench to reach the branches of the pods so you give up and keep walking into the Jardins del Real o Viveros towards the Museu de Belles Artes de Valencia. There are some park renovations being done so you have to turn before a café and then you go past a pretty blonde a bench looking up from her phone and you pass the cages of birds where the children and old people come to feed them through the grates. The chirping seems melodic but incessant too, almost what mania must be like when all the sounds are ringing at the same time so intensely that it’s hard to find the tune or rhythm. The chirping is like the white noise of people chattering in the courtyard of the University of Valencia Faculty of Letters where you will go tomorrow afternoon. Yes, in retrospect it’s the same chattering of beings trying to communicate to each other, each in their own code and style, with similar sounds and gestures, and how all communication starts to sound the same.

The sun is strong here and there is not a cloud in the blue sky above. You walk out of the gardens and under a road and then you are in the Jardi del Túria – Turia Gardens with its straight rows of jacaranda trees painting purple patches on a brown-beige backdrop of dirt paths and stone walls. This looks like a canal and that looks like an old Roman bridge and yes this used to the be where the River Turia made its sinuous way to the Mediterranean Sea until the massive flood of 1957 that went far into the city streets; after the 1957 Valencia flood, the local authorities decided to divert the river further outside of the city to avoid any further flooding. Plan Sur did just that by rerouting the river to go via a wider man-made canal south of the city that you drove along when you came in from the Valencia airport. In 1973, Plan Sur canal was completed: it’s all made of cement and it’s like a smaller version of the ones you saw in the Los Angeles, but this flood-control canal is covered with wild grasses and reeds that have grown in since the deadly Spanish floods of October 2024 when the river overflowed this canal too causing more casualties than 50 years ago. Now, there is no water coming down from the hills or so little that none is to be seen here, only the water coming up from the Mediterranean Sea but there is no zone of osmosis between salt and fresh water, just a dry riverbed. It’s a bizarre, estranging feeling to know that a flood devastated this area only months ago and now there is no water again.

On the other side of the converted Turia River, you can look back and see the beautiful blue-tiled dome of the Museum of Fine Arts that will be for another time and you see statues of religious men that maybe did something for society during their time, maybe that one there looks like San Jofre a little with his ring of hair and monkish frock and hands extended as if giving alms or showing that he has nothing left to give. You walk up the statue to check for a name but there are none, these are anonymous guys stuck on the parapet of an old stone bridge (Pont de la Trinidad – Puente de la Trinidad) in the sun. It’s rough being dedicated to something. And further on, you go through the famous Serrans Gate or Towers – Torres de Serranos built at the end of the 14th century to guard the medieval city from the barbarians out there, mainly the Moors at the time, and there is a dragon of course and a crenellated wall and the remains of a mini moat and square holes where they would pour down boiling oil or stones or other unpleasant things on the besieging attacking enemy. But now it’s all calm on the home front, there is no activity, just the warm air and breeze flapping the red and orange striped flag of Valencia on the tower.

“You should go to the Biblioteca Medica over in the old city on Plaza de Cisneros,” the guy at the first stop had said. He implied that there would be someone and some resources here. There is a little old lady at the reception and an exposition hall with old instruments. She looks disinterested and sends you to the second floor. The building was renovated and the old marble steps are smooth and worn on their edges where people trudged up and down over the centuries. You see the diagrams of human bodies on the walls of the stairway, this is a medical library after all, you think of all the people who may have walked up and down these stairs to make the edge smooth and rounded. How do you make marble look worn? On the second floor there is a door at the end of the hall and behind that door is a guy named José who seems to be have sitting there some centuries at his desk with the screen on in front of his face and the window open his left with a little breeze breaking the stifling air of the early summer heat, and the ageless endless view onto the beige buildings and terracotta rooftops as proof of human habitations having been here.

You explain the situation to José: the search for the earliest vestiges of hospitals, the influence of maristans from the Muslims, and the parallel emergence of places to care for the poor, sick and insane in Christian communities. José smiles and accepts the challenge to do a search for Father Jofré of Valencia and it seems like an amusing interlude into the apparent boredom of his work. But he doesn’t find much and explains that it’s getting late and that his boss will be in tomorrow and that maybe over at the Biblioteca Historica there will be more resources and results. You look around the little room with a few tables and chairs and some old books on metal racks and he smiles and says, yes this is the medical library. José writes some numbers and names and emails on a piece of paper and the search continues. Luisa, his supervisor, will find more sources and send them in the coming days, sources about the Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, also known more simply as the “Knights Hospitaller”, who built a hospital in Valencia after the Christian conquest from the Muslim of 1238.

Valencia is a hard-core Catholic city. You hear the classic church bells tolling across the terracotta rooftops at certain key times of day, but you also feel it in the naming of streets and the way people still go to church on a Wednesday evening at 6pm for vespers is one sign of devotion, but there is also a steady flow of people going to confess. As you walk into the historical site of the Iglesia San Juan del Hospital, there is a side room to the right where you hear the murmur of conversations being had in confession booths. Other believers are coming in and sitting on wooden benches looking at a statue of Christ drooping rather sadly from his cross. They wait silently for the others to finish confessing. People kneel first with the right knee. There is clearly a ritual here to follow. Religion is just a big ritual, and a universal source of solace.

In the main nave, you walk down towards the alter between the rows of benches and you ask the South American caretaker where to find the Muslim influence and Islamic star-shaped fountain. He is lighting candles for the service that is starting soon. “It’s closed”, he says and goes back to lighting candles. Someone must have the key, you insist and he looks annoyed and says you can come back tomorrow and pay for a guided tour, like everyone else, that’s the only way to get in, now it’s closed. That’s too bad, you say and look around the nave. There is another room on the left of the altar where people first dip down onto their right knee upon entering the Royal Chapel of Saint Barbara chamber where the believers then proceed to sit or kneel and cross themselves and intertwine their fingers of both hands together in holy prayer. This is happening today, twenty-one centuries after the birth of the guy of the cross. Christ Almighty…

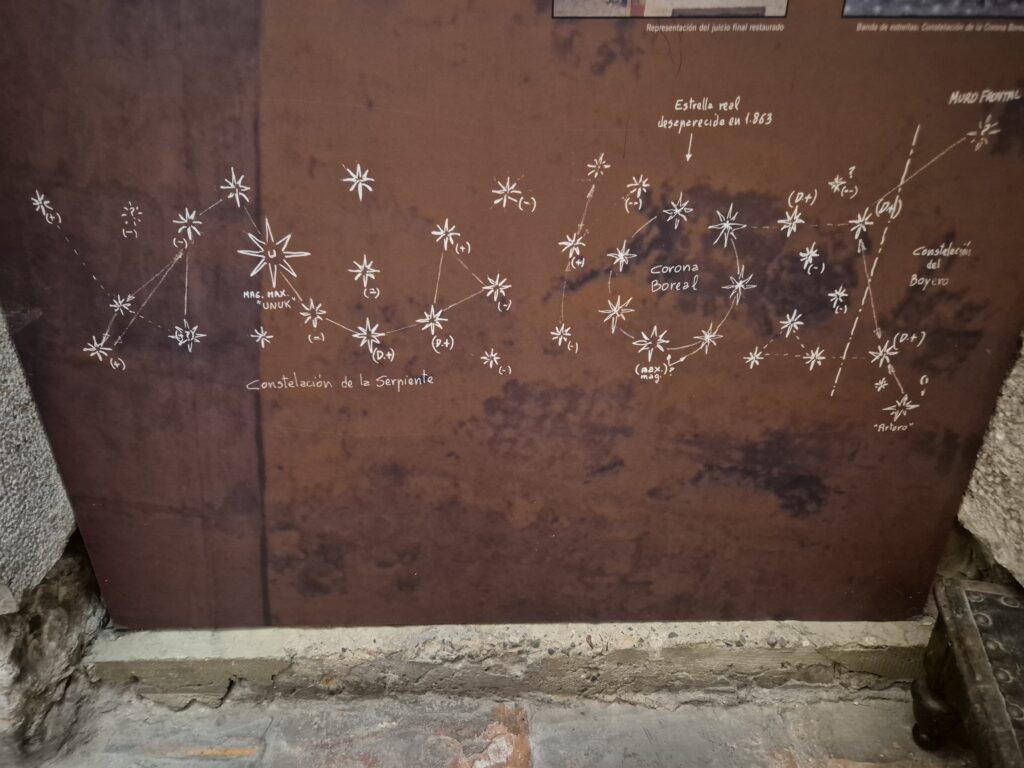

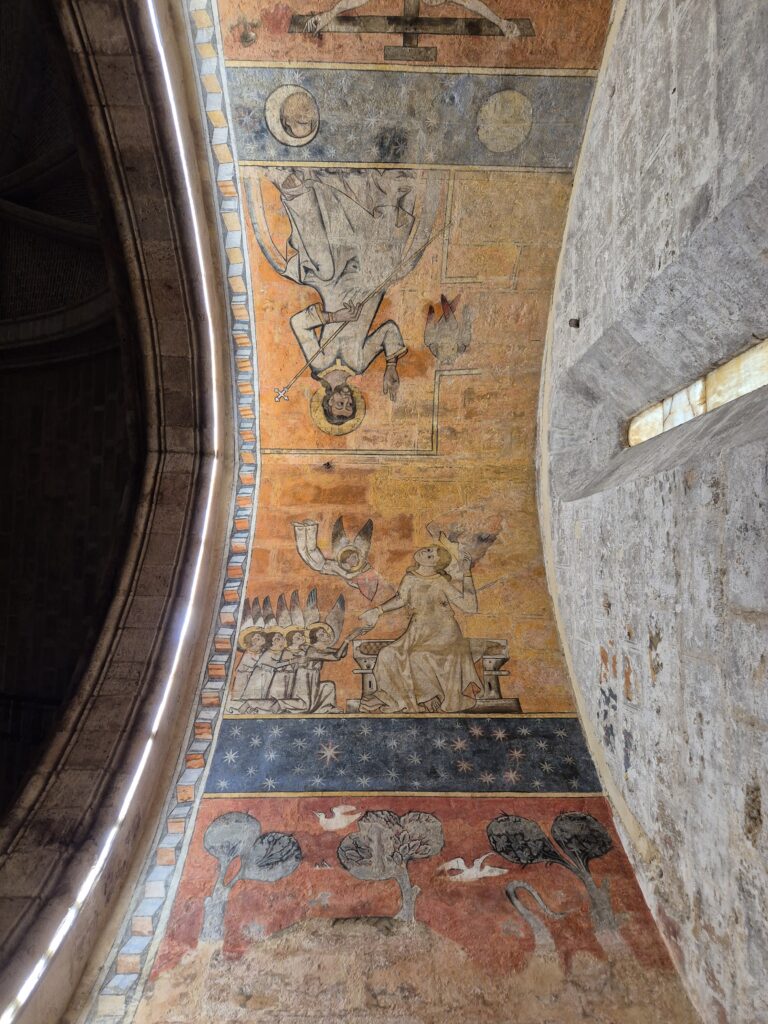

To the right of the altar, there are incredible frescoes on the inside part of a pointed arch that are from the 13th century. The archway is from the Chapel of Archangel Saint Michael. You think about what that means to be an archangel and you’re not entirely sure, except that Archangel Gabriel supposedly came down one night and helped Prophet Muhammad travel to Jerusalem to go up to the Heavens and back during his famous night journey, which seems somewhat unlikely as well. You prefer to look at the green tufts of trees and big white birds against the maroon sky and the band of bright stars above showing two constellations (Serpens and Corona Borealis) against an indigo night sky. On the descriptive plaque, there is an arrow pointing to the Real Star that disappeared in 1863 and you wonder how a star just disappears from the sky and then you realize it was a star from the fresco that detached after 700 hundred years of being hidden beneath cal (lime) plastering, and there is vertical design band of Islamic-influenced geometric boxes in full simplicity alluding to a scroll of sacred texts, a sequence of bibles, giving the contour of the arch a conclusive edge. And the real stars in the sky? Will they disappear someday too? Or are they destined to just keep moving further and further away forever? What you see in the night sky are remnants of the stars that were there before. What you see on the fresco band of blue is a representation of what remains from light years ago. And so, where do the real stars go?