The Nasrid Maristan

1365 AD / SPAIN

Built in 1365-1376 AD under the patronage of Muhammad V of the Nasrid dynasty, the Maristan of Granada is the only remaining medieval Islamic hospital in Spain. As in other Muslim cities at that time, the maristan was donated by the emir as a charitable building for those most in need of care in society. Located near the hammam (public bathes) on Calle Banuelo in the Darro River valley beneath the magnificent Alhambra, the the architectural foundation of the Maristan of Granada remains largely intact. Now a landmark within the famous medieval Albaicin neighborhood, Phase 1 (2017-2022) of the renovation included the restoration of the northern wall facing the Alhambra (see image above). The original lion fountain of the maristan can be seen in the Alhambra Museum that is located on the ground floor of the Palace of Charles V (see images below).

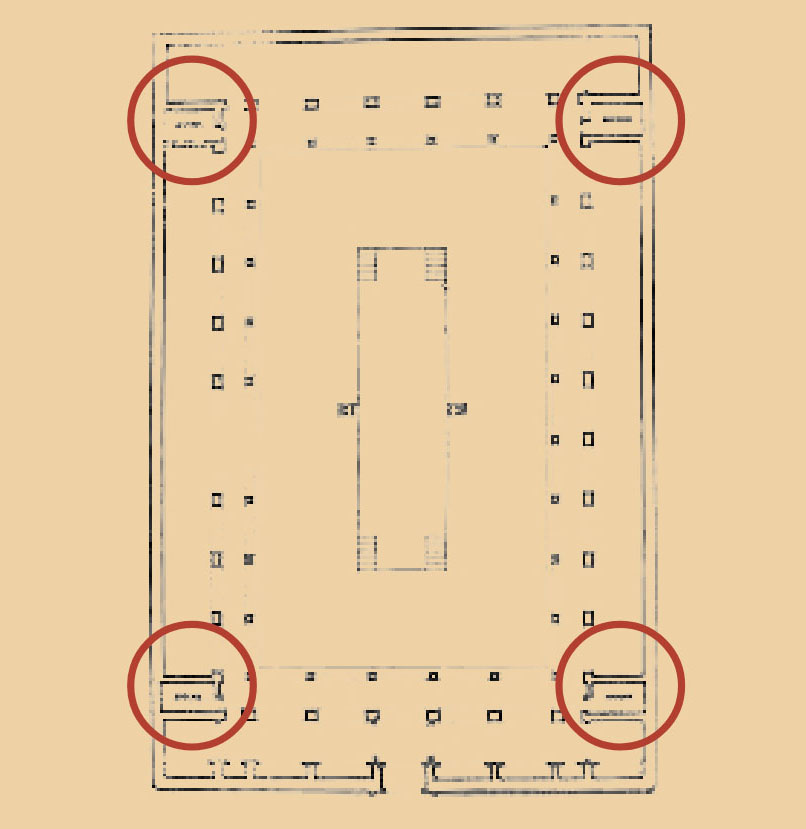

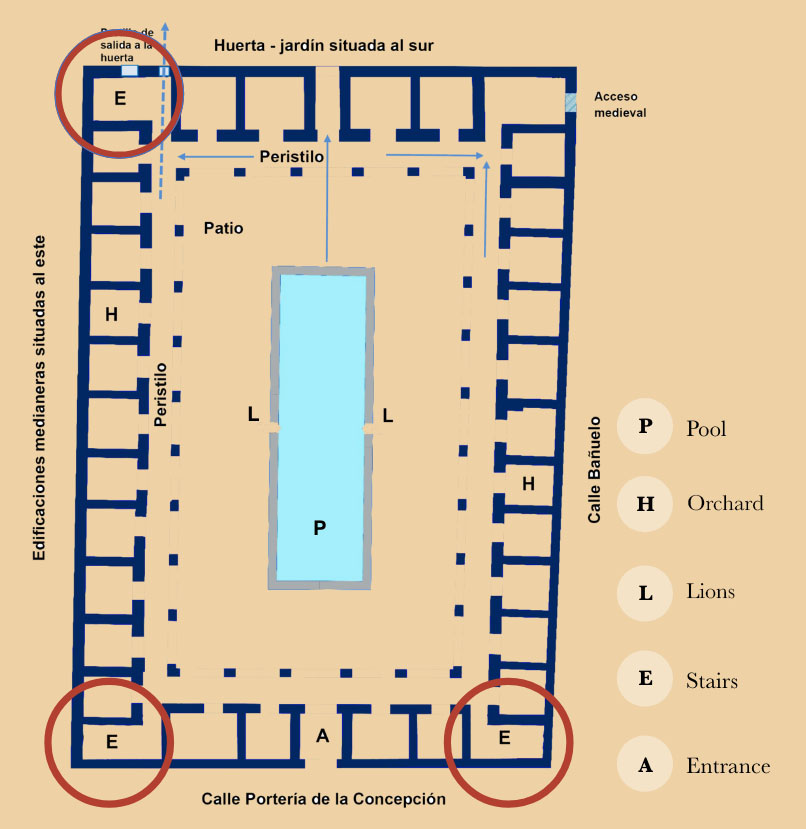

Architectural Floorplans

During the restoration of the southern door of the Nasrid Maristan, carried out from the end of 2019 until June 2022, the archaeological excavations showed that the stairs were situated in the corners of the building, not as depicted previously. The excavations also revealed that the rooms were not connected but rather separate spaces of some 8-9 square meters that were occupied by one or two patients, making the maristan more amenable for individual treatment.

Literary Quote

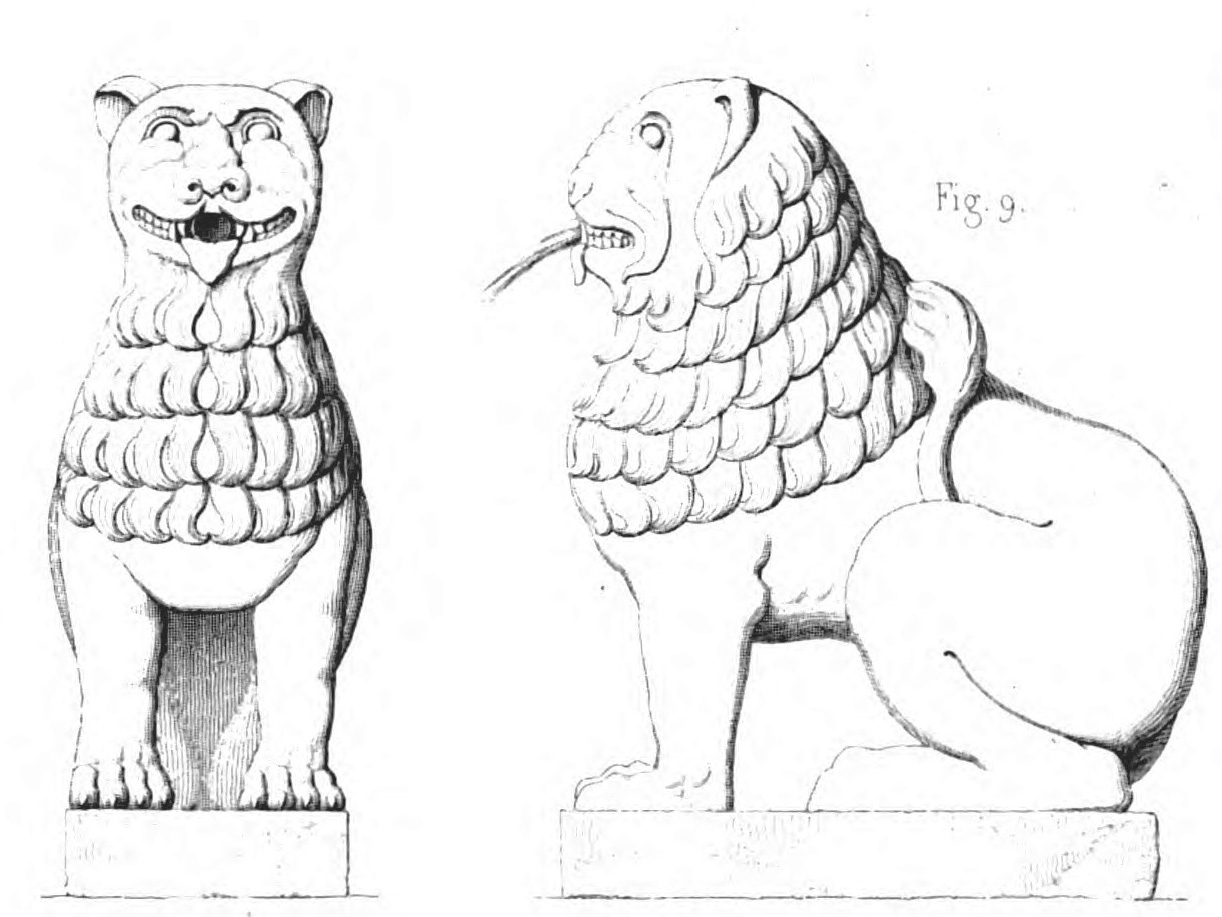

Dos leones de mármol blanco, labrados sucintamente sin intención realista y a la manera oriental, en posición sentada sobre sus cuartos traseros, vertían agua desde en centro de los lados mayores hacia la alberca central del patio. El hospital disponía de unas cincuenta salas, cada una de las cuales tenía capacidad para cuatro enfermos. Podían ser atendidos hasta doscientos pacientes, aunque nuna se había alcanzado ese número de ingresados. Las dependencias del piso bajo eran ocupadas por los hombres; las mujeres tenian reservada la planta superior.

Two white marble lions, carved succinctly without any realistic intention and in an oriental manner, sat on their hindquarters, pouring water from the center of the longer sides of the pool in the center of the courtyard. The hospital had about fifty rooms, each of which could host four patients. Up to two hundred patients could be treated, although that number had never been reached. The rooms on the ground floor were occupied by men; the upper floor was reserved for women.

The Maristan Lions

The two lions, sculpted in massive limestone blocks containing chert nodules, a material possessing great mechanical resistance, had water spouts in their mouths and were located on either side of the pool. The technique used in their construction and their location were linked with the iconography of the lion as an emblem of power. Learn more here.

The Foundation Stone

Located above the southern portal entrance of maristan, the foundation stone or tablet describes that the edifice was built by Muhammad V in 1365-1367 as a hospital and social institution for the poor and sick. Read more here.

Travel Blog

Granada 2, Spain

Over the course of June and into July, you had embarked on translating El perfume de bergamota in Almeria and had sent exploratory emails around to...Granada 1, Spain

When you type ‘maristan granada’ into a quick Google search, you do not expect so much information to pop up on your mobile phone...References

José Luis Gastón Morata, El perfume de bergamota, Granada: Almuzara, 2007 (2020, 5th edition).

Miguel Angel Ulecia Martinez, Asesio al Maristan Nazari, El complot del Cenidor. Granada: Editorial Nazari, 2020.

_________________________, El Maristan Nazari y sus hukama. Los Albencerrajes trucan su hikma. Granada: Editorial Nazari, 2021.

_________________________, El Espiritu del Maristan Nazari. La conspiracion de Bujada. Granada: Editorial Nazari, 2022.

Andrew Scull, Madness in Civilization – A Cultural History of Insanity, London: Thames & Hudson, 2015.

Adela Fabregas (ed), The Nasrid Kingdom of Granada between East and West. Leiden: Brill, 2021.

Michel Foucault, Histoire de la folie à l’âge classique, Paris: Gallimard, 1972.

Leopoldo Torres Balbás, “El maristan de Granada”, Al-Andalus, Madrid/Granada, Vol. IX, 1944, pp. 481-498.

Pedro Salmeron Escobar, “Consolidacion y restauracion del portico sur del Maristan nazari,” Alhondiga, La Revista de Granada, #39, julio-agosto 2023, pp.44-46.

SALMERON ESCOBAR, P., CAMPOS FERNANDEZ, F., GARZON OSUNA, D., PEREZ DE LA TORRE, R., “El Maristan nazari de Granada. Recuperacion de un monumento en una dificil encrucijada / The Nasrid Maristan of Granada. Restoration of a monument at a difficult crossroads.” Cuaderno de la Alhambra. 2020. #49. pp. 75-95. ISN 0590-1987.

CAMPOS MUNOS, A; GIRON IRUESTE, F. “El maristan de Granada. Escenario y simbolo de la medicina andalusi / The Maristan of Granada. Symbol and Institution of Andalusian Medicine.” Cuaderno de la Alhambra. 2020. #49. pp. 97-110. ISN 0590-1987.